Honduras experiments with charter cities

The Central American country has a bold plan to attract investment. It is not going well

ONE sunny Wednesday in Amapala, off the coast of Honduras, 33 working-age men settled themselves on rows of chairs on the main street under a tarpaulin to watch a football game. There was not much traffic to disrupt. The dilapidated town on the island of El Tigre had once been a bustling port, dispatching coffee and other commodities to Europe. Herbert Hoover and Albert Einstein thought the place worth visiting. But the German merchants and shipowners who had managed Amapala’s commerce left after the second world war; in 1979 the port moved to the mainland. The football fans now work intermittently as fishermen, farmers and drivers of three-wheeled mototaxis, most earning less than $2 a day. Some of the peeling pastel-coloured buildings bear signs in English, put up in expectation of a tourism revival that never happened.

Honduras’s government is promising a return to the glory days. In 2013 it announced plans to build a “megaport” in Amapala, along with a customs office and processing plants for exports such as shrimp, textiles and bananas. The money would come from private investors, who would be enticed by the establishment of three “employment and economic development zones” (ZEDEs). More ambitious than typical free-trade zones, these would be independent jurisdictions with their own laws, courts and police. The capital they attract would create jobs and relieve poverty. Rather than fleeing to the United States, Hondurans threatened by the country’s ubiquitous gangs could find security and livelihoods in ZEDEs.

The government has such faith in this idea that in 2013 it passed a law that adds ZEDEs to municipalities and departments as units of the republic. It is considering proposals for 20 ZEDEs across the country and has signed more than ten memorandums of understanding (MoUs) with investors, says Octavio Sánchez, one of the project’s leaders. Some are “ready to go—land bought, maps drawn and capital raised”, he says. The government may announce the first few projects at the end of August. They might be as small as a call centre or cover an entire city.

Sweet dreams are made of ZEDEs

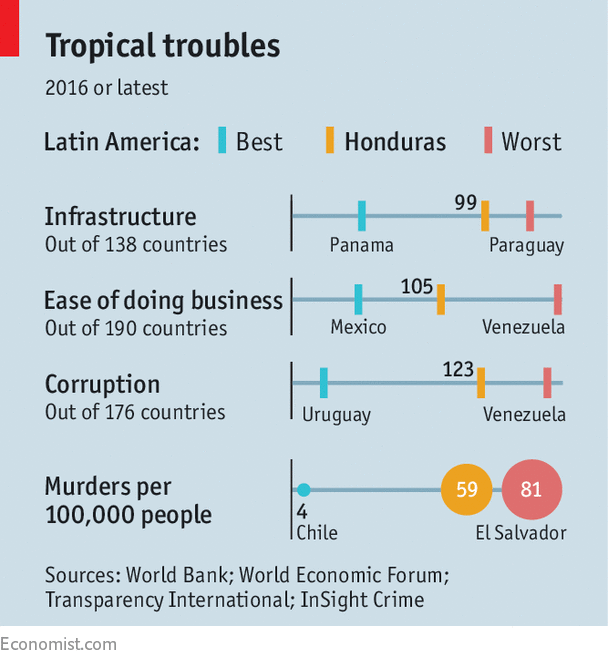

It is easy to see why Honduras might want to create enclaves of safety and efficiency on its territory. It is one of the world’s most violent countries; laws and contracts are spottily enforced; its bureaucracy is a hindrance rather than a help to its citizens; infrastructure is rudimentary and in poor repair (see chart).

The government’s proposal for overcoming these defects draws inspiration from the idea of “charter cities”, new jurisdictions on empty land that bypass weak institutions to attract investment and jobs. Paul Romer, now the World Bank’s chief economist, popularised the idea after noticing that autonomous cities like Hong Kong and Dubai became magnets for investment. In 2010 Mr Sánchez, chief of staff for Porfirio Lobo, Honduras’s president at the time, asked Mr Romer to help set up the first “model cities” after seeing a TED talk that he gave.

Like Dubai’s free-trade zones, ZEDEs are to be “seamlessly integrated into the city”, says Mr Sánchez. But they also hark back to an older model from Honduras’s banana-republic days, when the country in effect turned over swathes of territory to giant firms like the United Fruit Company. “Banana enclaves are an example of the successful functioning of models from other states,” says Ebal Díaz, the secretary of Honduras’s council of ministers.

But the plan to correct the country’s faults one ZEDE at a time is causing alarm. The zones can be created in thinly populated areas without the consent of the locals. Hondurans inside them will lose some rights. Under the law creating ZEDEs, just six of the constitution’s 379 articles must apply within them, points out Fernando García, a lawyer in Tegucigalpa, the capital. These do not include those underwriting such rights as habeas corpus and press freedom.

The project is beset by conflict between foreigners brought in to help monitor it and Honduran officials responsible for putting it into practice, and by strife among the Hondurans themselves. What decisions have been made and who has made them are a mystery to people outside the process, and even to some who are supposedly part of it. Outsiders assume the worst. A recent report by the Carnegie Endowment, a think-tank, calls Honduras “emblematic” of countries in which “corruption is the operating system” of networks formed by government, business and “out-and-out criminals”. The ZEDE saga suggests that such a system will have great difficulty in creating one that is free of its own shortcomings.

The ZEDE plan has its origins in a coup and the complicated politics that ensued. The government of Mr Lobo, who won hastily arranged elections after the army ousted a predecessor in 2009, passed a law creating a forerunner to ZEDEs. After the constitutional court struck down the law, saying it violated Honduran sovereignty, congress dismissed the four justices who had voted against it and amended the constitution to allow passage of the current “model-cities” statute in 2013.

By then Mr Romer had broken with the project (after he realised that the “transparency commission” he was supposed to chair would never in fact exist). But it still has plenty of political support. The current president, Juan Orlando Hernández, who is running for re-election, sees ZEDEs as a vote-winner. He recently posted on Facebook a (perhaps fanciful) map showing how they would transform Honduras into the Americas’ “logistics centre”. A motley group of foreign libertarians, who like the idea of lightly regulated mini-Utopias for enterprise, are still involved. The Inter-American Development Bank has said it may lend $20m to back their development.

Even after seven years of work, the scheme is as vague as it is ambitious. No one outside a small group knows what the first project will be. Agile Solutions, a Brazilian software firm, talks of investing $200m to open a “startup village” in Tegucigalpa, creating 6,000 jobs. Its Honduran boss, Carlos Cruz, sees the zone as a “blank slate”, which the company could use as a laboratory for new approaches to health care, education and tax.

Another candidate to be the first ZEDE is a public-private partnership with Canadian investors to create an “energy district” in Olancho department, where wood would be harvested for fuel. The ZEDE itself would be confined at first to a 1.6 square km (0.6 square mile) patch, which will be occupied by a power station. But it could eventually expand to an area covering 8% of Honduras’s territory and including 380,000 people. HOI, a Christian NGO based in the United States, is to provide health care and education from the outset in this “area of influence”.

After spending millions of dollars on feasibility studies for Amapala, South Korea’s development agency concluded that the area is not ready for a megaport. So the Honduran government decided to start with a tourism project that scoops into several fishing villages on the bay, plus factories and a customs centre nearby. Some proposed ZEDEs are based on “Plan 2020”, a master plan for the country drawn up by McKinsey, a consultancy. It suggests creating 600,000 jobs by attracting vehicle-assembly operations, call centres and other industries from Asia.

Even now, just how ZEDEs will work is a matter of argument among their supporters. The law places effective control in the hands of investors and a “technical secretary” who will administer each zone (and must be a Honduran citizen). They are answerable to an independent “commission for best practices” (CAMP). Civil and criminal cases will be adjudicated by special ZEDE courts, though it is not clear whether each zone will have its own or whether they will join a single parallel system. They could employ foreign judges to hear civil and criminal cases, just as Honduran football teams hire foreign players, suggests Mr Díaz. A “tribunal of individual rights”, guided by international conventions, will protect residents. Its decisions can be appealed to international courts.

But this governance structure is not settled; participants do not agree on what has been decided or even on who is part of it. The original CAMP, appointed by Mr Lobo, had 21 members, including Grover Norquist, an American anti-tax campaigner, Richard Rahn, then of the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington, DC, and Mark Klugmann, a former speechwriter for Ronald Reagan. This body met just once, in March 2015, on the resort island of Roatán.

According to Mr Sánchez and Mr Díaz, it has been pared down to 12 members. Seven are Hondurans from the ruling National Party; the five foreigners include Mr Rahn and Barbara Kolm, an economist with links to Austria’s far-right Freedom Party, but not Mr Klugmann. This group has been meeting secretly in Miami. But power is now exercised by a five-person standing committee led by Ms Kolm, who is the only foreign member.

Mr Klugmann denounces the sidelining of the original CAMP as “illegitimate” and illegal. Arnaldo Castillo, Honduras’s minister of economic development, denies that it has occurred. The argument over which CAMP is in charge is also about principle. Mr Klugmann thinks good governance matters more to investors than cheap labour and light regulation. He wants ZEDEs to perfect their institutional set-up before they start operations. Mr Rahn seems to be losing heart. He was “asked to try to bring in best practices of corporate governance”, he says. But it has been an “uphill struggle”. Although the CAMP is supposed to be independent, Mr Rahn has “the strong impression that there is government interference”.

Mr Sánchez’s Honduran faction seems more eager to sign deals, and more willing to cut corners. One proposal is for a public-private partnership with Conatel, the state-owned telecoms company. Its boss is Mr Díaz, who is also the member of the CAMP authorised to sign MoUs and the head of the agency that registers land titles. Mr Sánchez sees no conflict of interest in this accumulation of roles. “It’s the same government,” he says.

The fuzziness about governance will increase suspicion that ZEDEs are a further way to enrich an entrenched elite and erode the rights of ordinary Hondurans. The National Lawyers Guild, a left-leaning American NGO, fears that the CAMP and the technical secretaries will wield unchallengeable power over ZEDEs and the people who live and work within their boundaries. Once established, ZEDEs can seize land to expand the zones. That may provoke conflict: 90% of Hondurans do not have titles to their homes and scores have died in land disputes in recent years. Hondurans living in areas marked out for ZEDEs have little idea what is in store. “We have never been in the loop,” says Julio Ramírez, Amapala’s bespectacled town clerk.

It is possible that nothing will change in sleepy Amapala. Salvador Nasralla, the leading candidate to unseat Mr Hernández in elections on November 26th, says he would repeal the ZEDE law (though that would require a two-thirds majority in congress). The CAMP chaos may drive away investors. But if they come, the football aficionados of Amapala may learn what it is like to be guinea pigs in a daring economic experiment. Their little island will be in Honduras, but no longer of it.