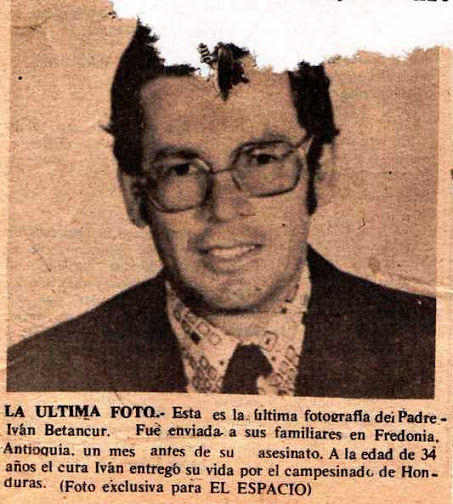

La última foto.- Esta es la última fotografía del Padre Iván Betancur. Fue enviada a sus familiares en Fredonia, Antioquia, un mes antes de su asesinato, a la edad de 34 años el cura Iván entregó su vida por el campesinado de Honduras (Foto exclusiva para EL ESPACIO)

Por:Juan Ramón Martínez.

En el primer trimestre de 1968, recibí en Choluteca la visita del diácono colombiano Iván Betancourt. Llegaba a la Colmena, centro de capacitación de Escuelas Radiofónicas, propiedad de la diócesis de Choluteca, entonces dirigida por monseñor Marcelo Gerin, miembro de la misión de los javerianos. Iván venía a conocer el trabajo que hacíamos con los campesinos, especialmente el programa de capacitación de líderes en que, usando el Método del Encaminamiento Operacional de la Acción Colectiva, con el padre Juan Pablo Guillte, buscábamos forjar líder que movilizaran la fuerza de los pobres de la comunidades rurales en dirección a la solución de sus propios problemas, sin depender del gobierno. Iván Betancourt había llegado en septiembre de 1968 a Honduras, estableciéndose en la diócesis de Olancho a cargo de monseñor Nicolás D´Antonio. Había nacido en Fredonia, Antioquia, Colombia, en el matrimonio de Luis y Felisa de Betancourt. Efectuó sus estudios secundarios en Cali entre 1954 y 1959. De Honduras, en 1970, regresa a Colombia en donde fue ordenado sacerdote en Fredonia. Fue asignado a Dulce Nombre de Culmí. De allí fue a Otawa, Canadá, a sacar una maestría en pastoral familiar (1974) y asignado a la parroquia de Catacamas, en donde desplegó un intenso trabajo con los movimientos católicos, especialmente la atención a las familias, estableciendo los “Laboratorios Conyugales” – que mucho ayudaron a los participantes, especialmente los que tenían problemas en el interior de sus parejas — y el de la Celebración de la Palabra, por medio del cual líderes religiosos dominicalmente en ausencia de sacerdotes, efectuaban la lectura de la Palabra de Dios y comentaban la vinculación de la misma con las realidades que enfrentaban en sus vidas individuales, familiares y comunales. Por su parte, el padre Casimiro Cyper había nacido en Medford, Wisconsin, en el seno de una familia pobre, el 12 de enero de 1941. Fue ordenado sacerdote franciscano conventual en la catedral de San Pablo en Minnesota el 29 de mayo de 1958. Llegó a Honduras, para atender las parroquias de Gualaco y San Esteban en el departamento de Olancho, lugares muy aislados y de difícil acceso, para entonces.

El 25 de junio de 1975, el padre Iván Betancourt viajando de Tegucigalpa hacia Catacamas, se detuvo a comprar combustible en la gasolinera que entonces estaba en un aserradero ubicado en el Valle de Lepaguare, – propiedad del señor Enrique Barh — fue capturado por fuerzas militares comandadas por el mayor Enrique Chinchilla. El padre Betancourt viajaba acompañado por María Elena Bolívar — joven nacida y residente en Cali, Colombia, trabajadora en un banco privado y novia de un hermano suyo con el cual proyectaba contraer matrimonio– y por la estudiante de la UNAH Ruth García Mallorquín, nieta de Justo García, antiguo capataz de los campos bananeros, compadre de mi padre y amigo cercano de mi familia, mientras vivimos, en el campo bananero de La Jigua, en el municipio de Arenal, en el departamento de Yoro. Ruth García Mallorquín aprovechaba el viaje del padre Betancourt para visitar a sus padres en Juticalpa. Betancourt y sus acompañantes, fue llevado esposado a la casa hacienda de los Horcones, propiedad de Manuel Zelaya Ordóñez – a quien apodaban “tres piezas” porque solo usaba zapatos, camisa y pantalón –, caudillo nacionalista (declaraciones de Jorge Arturo Reina, La Tribuna, julio 4 del 2016), convertido en liberal por Modesto Rodas Alvarado, en donde después de múltiples torturas y vejaciones difícil de narrar, sin ofender el oído de las personas, fue muerto a balazos inferidos por los implicados, sargento Benjamín Plata, mayor Chinchilla, Manuel Zelaya Ordóñez y Enrique Barh — junto a 10 personas más que habían sido capturadas por las autoridades militares en el Centro de Capacitación Santa Clara: Máximo Aguilera, Lincoln Colman, Arnulfo Gómez, Alejandro Figueroa, Fausto Cruz, Francisco Colindres, Óscar Ovidio Ortiz, Bernardo Rivera, Roque Ramón Andrade y Juan Benito Montoya. El Centro había sido cedido por el obispo de la diócesis a las organizaciones comunales del departamento de Olancho. Eran oficinas de las Escuelas Radiofónicas, Cáritas de Honduras, de UNC, de la Cooperativas de Consumo que tenía su bodega central allí y el espacio en donde se ofrecía capacidad a los dirigentes de las comunidades rurales y de las ciudades olanchanas. El gerente de la bodega central de la Cooperativa de Consumo, era Lincoln Colman. Durante el asalto, los ejecutores saquearon todos los bienes de consumo que había allí. Es decir que, además de capturas y asesinatos, los asaltantes y sus compinches, ejercieron el saqueo de los bienes de los campesinos. Apenas pudo rescatarse, me refiere Fausto Erazo Camacho que era para entonces, el coordinador nacional del movimiento de las cooperativas de consumo, una de las bodegas de frijoles propiedad de la UNC que, no pudieron llevarse las autoridades convertidas en delincuentes.

La marcha campesina

El movimiento campesino social cristiano, posiblemente el más fuerte y organizado de toda la historia del país que, entonces contaba con la simpatía y el apoyo de parte de la Iglesia Católica del país – había decidido realizar una “marcha Campesina” que, desde diferentes puntos, convergería en la ciudad de Tegucigalpa para exigirle reivindicaciones al gobierno de Juan Alberto Melgar que ilegalmente ejercía la función de jefe del Estado, nombrado por quienes habían asumido para entonces la soberanía popular: el Consejo Superior de las Fuerzas Armadas. La idea no era original. Tenía un antecedente que algunos líderes sociales cristianos conocían: la marcha sobre Roma de Benito Mussolini. Y en Honduras, la uso en 1972 Osvaldo López Arellano, contando con la complicidad de Reyes Arévalo, presidente de la ANACH, — la más fuerte organización campesina para entonces — para precipitar el golpe del 4 de diciembre de 1972, que provoco la caída del presidente Cruz Ocles. De forma que para los militares que rodeaban a Melgar, La Marcha Campesina tenía una evidente orientación política que era necesario neutralizar. Cosa que hicieron muy bien, de forma pacífica, en casi todo el país. Las comunicaciones funcionaron muy bien en todos los departamentos del país, menos en Olancho en donde Chinchilla incurrió en el delito para evitar el avance de la marcha campesina que, nunca trascendió las fronteras departamentales siquiera.

La reacción del gobierno de Melgar Castro

En razón de lo anterior, el gobierno del jefe de Estado Melgar, ordenó que se detuviese la marcha. En casi todo el país, el operativo funcionó: los campesinos fueron bajados de los buses y regresados a sus lugares de origen, se colocaron retenes en puentes para detener pequeños camiones que conducían personas sospechosas, etc. etc. Menos en Olancho. Había allí una fuerte alianza entre los ganaderos y los militares, enfrentados a los dirigentes campesinos que tienen tras de una gran organización de cooperativas de consumo, bases muy bien entrenadas y movimientos auxiliares como las Escuelas Radiofónicas y los Clubes de Amas de Casa que ya estaban siendo transformados en la base de la Federación de Mujeres Campesinas de Honduras. Además, había un fuerte rechazo, artificialmente montado en los grupos pudientes de Olancho, en contra de la Iglesia Católica. La alianza de los militares con los principales dirigentes ganaderos – Juan Zambrana, Manuel Zelaya Ordóñez, entre otros – y el mayor Enrique Chinchilla, todavía no está suficientemente estudiada. Por su especificidad y su anormalidad. Porque solo allí, en Olancho se actúo con tal saña, violencia e irrespeto a la ley por parte de los militares. En ningún otro lugar del país se produjo un incidente tan doloroso y que tanta vergüenza ha provocado entre todos los hondureños. Fue un crimen atroz, con todos los agravantes y además, cometidos por la autoridad en contra de sacerdotes, personas particulares, una extranjera incluso y líderes campesinos. Los intentos para explicar tal conducta criminal, solo se pueden hacer desde la anormalidad psicológica y la arrogancia del poder. O fruto de la personalidad del mayor Chinchilla, su incapacidad para entender las órdenes de sus superiores y el consumo de estupefacientes, para mantenerse activo. El comportamiento de los ganaderos cómplices no es extraño e incomprensible, porque creían que sus propiedades estaban amenazadas. Y hombres violentos, creyeron que la violencia con los militares, tenía la impunidad asegurada. Adicionalmente hay que decir que Melgar simpatizaba con el social cristianismo de tal forma que, adicionalmente por razones de amistad había nombrado asesor de su gobierno al Ing. Vicente Williams Agase, a Fernando Montes Matamoros como ministro de Recursos Naturales y a Lidia Williams de Arias como ministra de Educación. Los dos primeros, por razones obvias, se opusieron a la Marcha Campesina, porque anticipaban confrontaciones en Olancho, en donde ya se había producido el primer encontronazo violento entre campesinos y terratenientes con saldo de varios muertos en el lugar llamado La Talanquera, tres años antes. No cabe duda que los sacerdotes de la diócesis apoyaban como obligación evangélica a las organizaciones campesinas, justificaban el reclamo de los más pobres por una vida mejor; pero no participan en la organización y mantenimiento de la Marcha Campesina sobre Tegucigalpa, como algunos desinformados creyeron. Tenemos evidencia que la participación del padre Iván Betancourt es mínima, casi marginal en una zona de elevada organización campesina como es Catacamas. Y la del padre Casimiro Cyper es posiblemente inexistente, tanto porque Gualaco era en términos de organización social, una zona de frontera y su sacerdote – recientemente llegado al país — todavía no había terminado de entender el tipo de conflicto y formas de lucha usados por los campesinos. Por lo que estaba menos involucrado en apoyarlos que otros colegas suyos, ubicados en el resto de las parroquias del extenso departamento de Olancho, el más grande y despoblado del país. Con exceso de tierras y por supuesto, extensiones sin cultivar por nadie.

La denuncia de José Ochoa Martínez y el arzobispo Héctor Enrique Santos

Chinchilla, después del crimen cometido, pidió dinero a los ganaderos – los que lo aportaron generosamente – para montar una campaña de desinformación, propalando la especie que los desaparecidos, incluidas las dos señoritas asesinadas, se habían internado en las montañas para iniciar mediante la técnica de guerra de guerrillas, la lucha en contra del gobierno. Uno de los periodistas a los que se le ofreció dinero fue José Ochoa Martínez el que, al darse cuenta que era una trama muy burda en un clima noticioso que reclamaba explicaciones más lógicas, creyó que era su deber darle a monseñor Héctor Enrique Santos, no solo la información referida al intento de conseguir su respaldo periodístico a cambio de dinero, sino que además referirle que las 14 personas habían sido asesinadas. Monseñor Santos y la Conferencia Episcopal, pidieron una investigación del asunto y mostraron su dolor ante lo ocurrido.

La Comisión de Investigación de las Fuerzas Armadas

El Consejo Superior de las Fuerzas Armadas creó una comisión integrada entre otros por el coronel Amílcar Zelaya Rodríguez, que rindió un informe contundente sobre los hechos, confirmando el asesinato de 14 personas, el depósito de sus cadáveres en un pozo de malacate de la hacienda de Manuel Zelaya Ordóñez, al cual agregaron varias bolsas de cal viva, tierra de los alrededores y usaron tractores para aplanar el terreno, de tal manera que nadie pudiera imaginar que alguna vez allí había existido un poso de malacate. Después que los involucrados confesaron los crímenes, se procedió a desenterrar los cadáveres. El de María Elena Bolívar regresó a Colombia. Ruth García fue enterrada en Tegucigalpa. En la UNAH hay un busto suyo, el único de todos los mártires del acto más violento de toda la historia del país, que ha sido recordada y honrada por sus compañeros universitarios. Los sacerdotes y los dirigentes campesinos fueron enterrados en varias localidades del departamento de Olancho, entre la pena y el estupor de miles de personas que constataban asombrados el grado de salvajismo que provocaban las autoridades sin ley, sobre los ciudadanos indefensos del país. Iván Betancourt fue enterrado fuera de la iglesia de Catacamas, en uno de sus costados. El padre Casimiro en el interior de la iglesia de Gualaco. De ninguno de los dos y de nadie más, hay un monumento que recuerde su martirio. La cruz que los campesinos colocan en el lugar donde fueron arrojados al fondo del pozo de malacate, los propietarios del suelo, las derriban y destruyen. Para que no quede huella.

El rompimiento entre las FF AA y su pueblo se inició peligrosamente y en muchos oficiales, se desarrolló el sentimiento que era el momento de regresar a sus tareas profesionales, devolviéndole la soberanía al pueblo y el gobierno a los políticos. Melgar pidió y obtuvo la renuncia de Williams Agase y Montes Matamoros e inicio, su declive que al final, terminaría con la forzada renuncia pedida por el Consejo Superior de las Fuerzas Armadas, del cargo de jefe de gobierno en agosto de 1978. Dos años después, los militares algunos a regañadientes, convocaron a elecciones generales, las que fueron ganadas por los liberales que compitieron contra los nacionalistas que cargaban bajo sus espaldas los errores de 17 años de gobierno del “amachinamiento” entre López Arellano y los dirigentes nacionalistas encabezados por Ricardo Zúniga Agustinus.

El retraimiento definitivo de la iglesia, la rendición de la jerarquía y el abandono de la pastoral social de la tierra y dejo atrás, el olor de sus ovejas.

La Conferencia Episcopal de la Iglesia Católica hondureña no pudo asimilar el golpe. Ni entender a la luz del Evangelio, el sentido de los hechos ocurridos La confrontación violenta, los asesinatos de los dos sacerdotes, las dos señoritas y los 10 campesinos en Olancho, no pudieron ser asimilados por la jerarquía católica que reaccionó con exagerada mansedumbre, se distanció de la organización campesina, rompió relaciones con el PDCH y removió de sus filas a los seglares que habían tenido alguna relación con los acontecimientos. Dejó de oler a ovejas, como va a decir mucho tiempo después Francisco, el Papa jesuita nacido en Argentina y que ahora vive en Roma. Y lo peor, retiro de la silla obispal a Nicolás D’Antonio que fue exiliado a los Estados Unidos, su país de origen. Las parroquias fueron abandonadas. Contrario a la historia del cristianismo que siempre se ha agigantado ante la sangre de sus mártires, la Iglesia Católica, se acobardo y cedió ante la petición de los militares, cuya amistad considero mucho más importante que cualquiera otra consideración doctrinal. Por ello es que fuera de Olancho, ni Iván Betancourt y Casimiro Cyper, son considerados como mártires de la iglesia hondureña, pese a que entregaron su vida por razón de su fe. La Iglesia Católica hondureña, a partir de junio de 1975, empezó a declinar numéricamente, de forma que a estas alturas incluso, representa menos del 50% de los que se consideran religiosos en el país. Superada por los evangélicos, por primera vez en su historia. Cada 25 de junio se honra a los mártires, pero solo en Olancho. En el resto del país, incluso no se les considera ni siquiera hermanos asesinados por su fe y su devoción por los pobres. Ni se reza una oración por su descanso eterno.

Los asesinos principales, tuvieron mejor suerte. Zelaya Ordóñez, padre del expresidente Manuel Zelaya Rosales y Enrique Barh, encausados, ingresaron en la cárcel y estuvieron en ella, menos de un año. El primer acto de Roberto Suazo Córdova, católico confeso y santero de mucha fama internacional, desde la Asamblea Constituyente, emitió un decreto de amnistía que les permitió salir en libertad. El mayor Chinchilla fue enviado a un cargo de agregado militar en Europa. Según refieren, actualmente, reside pacíficamente tranquilo en San Pedro Sula. No fueron tan afortunados, el sargento Plata, que murió víctima de un atentado del que nunca se supo quiénes fueron sus autores. Ni tampoco el obispo Nicolas D Antonio, que fue destituido de su diócesis, castigado y enviado a una olvidada parroquia en los Estados Unidos. Allá, viejo y abandonado, reza con amorosa devoción, por el alma de quienes fueron víctimas del más horrendo crimen de la historia de Honduras.

Tegucigalpa, julio 3 del 2016

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/opinion/editorials/2011/08/16/canada_backs_profits_not_human_rights_in_honduras/harper_inhonduras.jpeg)